William Cobbing: Heads, but not faces

The Kiss, 2004, video, 3:33 min.

I saw this short video at Matts Gallery in London in November 2012. In the video, the two people are joined at the head; you see their hands moving across the clay, and hear the squelch of the wetness. It had a deep affect on me. I guess my current work is my personal response to it.

William Cobbing is Senior Lecturer in Fine Art at Wimbledon College of Art. He is an artist who works across performance, sculpture, video and installation.

Heads feature frequently in these performances but never as faces. Instead, individual identity is shrouded by a crazed and mucky parallel of the pixilation that newsroom editors employ in controversial situations to “protect” the speaker from personal recognition. The shifting alluvial mask that obscures two heads in The Kiss, Cobbing’s film of the eponymous action, materialises the look of love into a tactile mass, a cloggy marl that hands knead, model, smear and spread noisily, glutinously and messily.

On another occasion he buries a head in a ball of concrete while the body that owns it stands facing a brick wall, pressed into a column of the same concrete piled against the elevation. Whether the concrete originates from the head or from the wall is a detail that Cobbing leaves to the viewer’s imagination because, having allowed the adhesive outcrop to dry, the anonymous figure starts picking at the sediment with a chisel and hammer to bring about his own liberation.

Perhaps this work represents not a nightmare but taps at dream-life generally, at its incongruities and ludicrousness, those irrational connections that play out seamlessly in the demented narrative from which the sleeper awakes momentarily confused and distressed. Head cases, indeed, and Cobbing’s documentary habit unleashes a sensation that this whole enterprise has strayed into an art setting through clinical ancestry.

— Martin Holman, Miser & Now,

‘It shouldn’t happen to a dream’,

Issue 11, 2007, pp. 32-39

Energy yes! Quality no!

I am not interested in failure. I do not want to fail, but I do not exclude that I can fail, that my work can fail. But it is not an obsession for me. I am interested in energy, not quality. That is why my work looks as it looks! Energy yes! Quality no!

Thomas Hirschhorn interview, Flash Art no. 238 (Oct. 2004)

Thomas Hirschhorn’s ideas about energy being more important than quality were passed to me by Dale Holmes, when I was having a moment of doubt.

Hirschhorn seems to hit the nail on the head. Who can say what the measure of quality in art is, particularly when that measure changes from one year to the next? It seems like a fool’s game to try and chase after notions of quality.

Energy, on the other hand, we can know; if we look deep inside, we know whether a particular work, or a line of enquiry holds energy for us or not. And this is certain: my current line of artistic enquiry holds a lot of energy for me. I am excited by it – I think about it all the time.

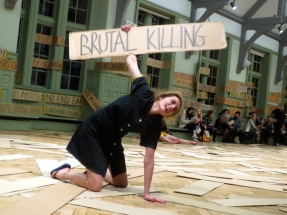

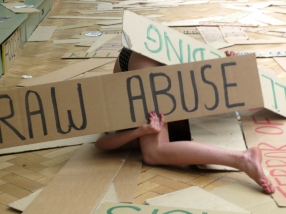

La Ribot’s Laughing Hole

Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester on Thursday 12th March 2015

One of the most disturbing pieces of art I’ve ever seen. For several hours, three flexible young women pull placards with darkly suggestive words from the floor and hold them aloft, their bodies contorted in various ways. But here’s what you can’t see in the photos: they are laughing, and there’s a recorded soundtrack of laughter pulsing loudly through the space, sometimes with an accompanying static-drone.

Sometimes the dancers came right up next to me, touching – in one case, with a placard that read “FEED ME” – and looked me straight in the eye, smiling and laughing. I hadn’t a clue what to do, laugh along, sit there impassively, or look away; every option seemed wrong.

The dancers were remarkable not only for their strength and suppleness, but for the way they kept up the laughter and smiling in a remarkably convincing way. I was there from 7pm until 10pm (it started at 4pm) and the three that I saw didn’t stop once.

I was particularly interested to see this piece, my first time seeing La Ribot’s work live. Being a long durational live art event, with audience free to come and go as they please, I felt it might inform my own work.

Ocularcentrism

Ocularcentrism

A perceptual and epistemological [epistemology = concerned with the theory of knowledge] bias ranking vision over other senses in Western cultures. An example would be a preference for the written word rather than the spoken word. Both Plato and Aristotle gave primacy to sight and associated it with reason. We say that ‘seeing is believing’, ‘see for yourself’, and ‘I’ll believe it when I see it with my own eyes’. When we understand we say, ‘I see’. We ‘see eye to eye’ when we agree. We imagine situations ‘in the mind’s eye’. ‘See what I mean?’ Commentators such as McLuhan argue that literacy and the printed word have played a key part in the elevation of the eye to such primacy as a way of knowing.

from Oxford Dictionary of Media and Communication

****

The hegemony of vision has been reinforced in our times by a multitude of technological inventions and the endless multiplication and production of images.

Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses

****

The fundamental event of the modern age is the conquest of the world as a picture.

Martin Heidegger, The Age of the World Picture

****

“As a society, we put more weight in vision, and to a lesser degree hearing, because the other three senses—taste, touch, smell—are so clearly sensual, and we’re all scared of the sexy…

And so, we live in an ocularcentric world. But what does this really mean? Well, it means that we appreciate things visually and we appreciate visual things. We prioritize the visual more so than any other sensory experience and perception.”

Lily Hoang, http://htmlgiant.com/random/ocularcentrism-storytelling-and-the-internet/

****

Are we all scared of the sexy?

Chris Beale 13.3.15

The effect of blindness on visual imaging

In June, I intend to perform my live art work blindfolded, or encased in clay, for several hours each day. I am curious to find out if this voluntary blinding will enhance my other senses, during my explorations of the material properties of clay. But how much will I really be able to let go of my visual sense, when it is normally so dominant? Even while sightless, will I merely spend my time imagining what the clay looks like? And will my other senses really be enhanced during such a limited period of time?

Oliver Sacks writes that changes can come quickly: “In June 2003, Italian researchers published a study showing that sighted volunteers kept in the dark for as little as 90 minutes may show a striking enhancement of tactile-spatial sensitivity”.

Furthermore, he reports that “Alvaro Pascual-Leone and his colleagues in Boston have recently shown that, even in adult sighted volunteers, as little as five days of being blindfolded produces marked shifts to non-visual forms of behaviour and cognition, and they have demonstrated the physiological changes in the brain that go along with this.” So, physiological changes to the brain can come in only five days.

One way of looking at this issue, so to speak, is to consider the experience of sighted people who become blind.

People who lose their sight in infancy retain no memories of seeing, they have no visual imagery. But what of those who lose their sight in later childhood or adulthood?

John Hull, an American professor of religious education lost his sight at the age of 48, after a period of decline. He recounted that he lost all visual images and memories in just two or three years. For example he had no memory of which way round a number ‘3’ went. (Book: Touching the Rock: An Experience of Blindness). Hull calls this imageless state ‘deep blindness’.

Although at first distressed by the fading of visual memories, he soon accepted it with equanimity; he regarded this loss of visual imagery as a prerequisite for the heightening of his other senses – a unique form of perception, a precious and special mode of being. “Increasingly, I am no longer even trying to imagine what people look like… I am finding it more and more difficult to realize that people look like anything, to put any meaning into the idea that they have an appearance”.

In contrast, other people who lost sight in adulthood never lose their visual images or memories, even after decades of blindness. Zoltan Torey, an Australian psychologist who lost his sight in an accident at the age of 21 (Book: Out of Darkness) wrote that he passionately held on to light and sight, to maintain – if only in memory and imagination – a vivid and living visual world, meticulously constructed.

He became able to multiply four-figure numbers by each other, like on a blackboard, visualising the operation in different colours.

Another person who held onto her visual sense was Arlene Gordon, a former social worker. She said, “If I move my arms back and forth in front of my eyes, I see them, even though I have been blind for more than thirty years” – moving her arms was immediately translated into a visual image. Even listening to talking books made her eyes tire, with sound transformed into lines of print.

Oliver Sacks reckons that whether you held onto visual images or not would depend on which way you are predisposed – pointing out that there are huge variations in visual imagery and visual memory among the sighted. I have a hunch that I am more predisposed to be a John Hull than a Zoltan Torey or an Arlene Gordon. My powers of visual imaging are not that strong; I’m utterly unable to draw people unless they are in front of me, for example. And many times I am very happy to close my eyes, and feel touch, proprioception and gravity more intensely. There are times when I’m dancing slowly with someone at 5 Rhythms or Contact Improvisation, and my eyes close naturally, unbidden. I do not then translate my sensations into visual images, like Arlene Gordon with her waving arms. On the contrary, I positively enjoy letting go of my visual sense, as I enter a realm that feels more intense and connected.

J. Lusseyran, blinded in an accident when eight, was a French resistance fighter (book: And There Was Light). He railed against the “idol worship” of sight, saying that blind people have a better sense of feeling, of taste, of touch, of smell. All of these, he says, blend into a single fundamental sense, a deep attentiveness, a sensuous, intimate being at one with the world which sight, with its quick, facile quality, continually distracts us from.

12.3.15

Source:

Oliver Sacks, The Mind’s Eye: What The Blind See, in Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Culture Reader, ed. David Howes, Berg (2005)

More on Haptic Perception

Haptic perception is about the active exploration of external things through touch. The most common way we do this is by feeling with our hands. When we are using haptic perception, our hands, arms and perhaps other body parts move, and our attention is directed outwards towards the object and its properties: its size, weight, contour, surface and material characteristics, consistency and temperature.

(By contrast, passive contact with touch is tactile perception. So, being touched by something or someone tends to focus our attention on our own subjective bodily sensations. If you hit my arm with a hammer, I’d probably be thinking about how my arm felt, not the finer details of the hammer.)

How does haptic perception work? The haptic system combines sensory information derived from two sources:

(a) Receptors embedded in the skin – cutaneous inputs. They are all over body, beneath both hairless and hairy skin.

(b) Receptors embedded in muscles, tendons and joints – kinesthetic inputs. Perception of limb position and limb movement in space.

Source:

Haptic Perception: A Tutorial, Attention, Perception and Psychophysics, 2009, 71 (7) pp. 1439 – 1459.

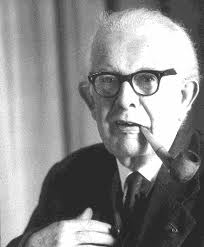

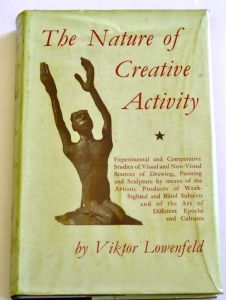

Viktor Lowenfeld: Visual Perception and Haptic Perception

Viktor Lowenfeld, Austrian, (1903-1960) Professor of art education at Pennsylvania State University. While previously in Vienna, served as director of art in the Blind Institute.

The Nature of Creative Activity (1939) postulated two opposite types of perceptual orientation, haptic and visual, which are reflected in artistic production. Evolved from many years of observation of children’s art work in Austria and America. They are opposite types, but people will be on a spectrum. Most normal-sighted people are of the visual type, but a sizeable minority aren’t – perhaps up to 25%.

Lowenfeld believed these differences to be innate, deeply-rooted psychological characteristics; he did not believe it is possible to move from one mode of perception to other. Art teachers must always cater for both.

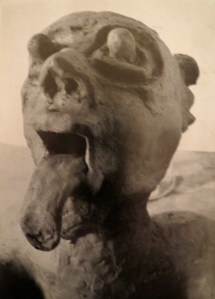

Haptic:

Concerned with bodily sensations and subjective experiences in which he or she is emotionally involved

Subjectively and emotionally oriented, relying more on kinesthesis than vision.

Feels as a participator; the self is projected as the true actor of the picture

Confines his world to things that can be perceived by means of touch or bodily sensations

Does not analyse the world but is concerned with projecting his inner world into the picture

3D space and distances are shown by a “perspective of value only” e.g. objects drawn larger or smaller in relation to their emotional significance rather than apparent distance from observer

Haptic perception is “the synthesis between tactile perceptions of external reality and those subjective experiences that seem to be so closely bound up with the experience of self” (The Nature of Creative Activity, p. 82).

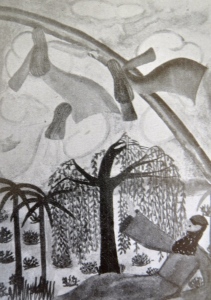

“Moses strikes the rock that water may flow”

“Moses strikes the rock that water may flow”

Visual

Feels more like spectator than participant. Seeks experience outside the body.

Concerned more with an objective analysis of visual detail.

Representational work is portrayed from the point of view of an observer who is concerned with the appearance of things rather than with their subjective meaning

Analytical approach – a spectator who finds his problems in the complex observation of the ever-changing appearance of shapes and forms; who seeks to analyze this total impression into a detailed or partial impression, and to synthesise these parts into a new whole.

“Moses strikes the rock that water may flow”

“Moses strikes the rock that water may flow”

—–

This way of understanding perception is extremely interesting to me. Unlike Lowenfeld, I do believe it is possible to shift from one mode of perception to another. I believe this because over many years my own perception is shifting, from an entirely visual one towards one where visual and haptic perceptions are much more evenly balanced. It’s something that I not only welcome, but positively encourage. The shift is bound up with my regular engagement in various activities over a period of more than a decade: dance, meditation and yoga.

My last two major artworks were both performances done ‘blind’, in gear which did not allow me to see, making me reliant on touch and kinesthesia. I intend to do the same in my degree show.

Emily Speed

Just yesterday I was marvelling at this artwork by Emily Speed, Inhabitant, in a book called Doppelganger: Images of the Human Being. I love the way it hits you first as a sculpture, and then you notice the feet. It is great to think of this person within their own architectural cityscape.

And then who should come and give a talk at Hallam University today…. none other than Emily Speed.

She said she made it while in Linz, Austria, and she went for an hour-long walk around the city whilst inside it, with someone shouting directions. She said it was an important work for her, a breakthrough.

One of her inspirations was a book by Japanese novelist Kobo Abe, The Box Man, about a man who withdraws from life and lives with a cardboard box over his head. Sounds interesting.

Creating identity

Yesterday I was talking to Zee at Zandra Ceramics, located at 35 Chapel Walk in Sheffield [photo above]. Zee was saying that being a successful artist is all about creating an identity. She said remarkable things happened when she changed her identity from Sandra to Zandra, or Zee for short. Suddenly she was accepted for shows, where before she’d had no joy. Some of these were the very same events that had refused her work when she was called Sandra. I find that rather shocking.

I find it shocking, and yet at some level I understand it too. “Zandra” has some kind of impact that “Sandra” just doesn’t have. It feels more exciting, creative, sexy, modern. It stands out. Zee said she chose it partly because, on a list of people, it would occupy an important position; at the end of the list, for sure, but much less likely to get ‘lost’ than someone in the middle.

We’re into the murky world of marketing here, of course. Not a territory I feel at home in. But if you’re a creative type, why not be creative with your artistic identity?

It made me wonder what I would name myself. As I learnt from ‘Circumbendistuff’, inventing a new word is a good idea because if people google it they find you immediately. I’ll give it some thought.

Zee has a ceramics exhibition planned for May, and I am going to do some clay-related performance art in the space over two days. It feels great to be putting my work out into new spaces, with relevant connections.